- The Incline

- Posts

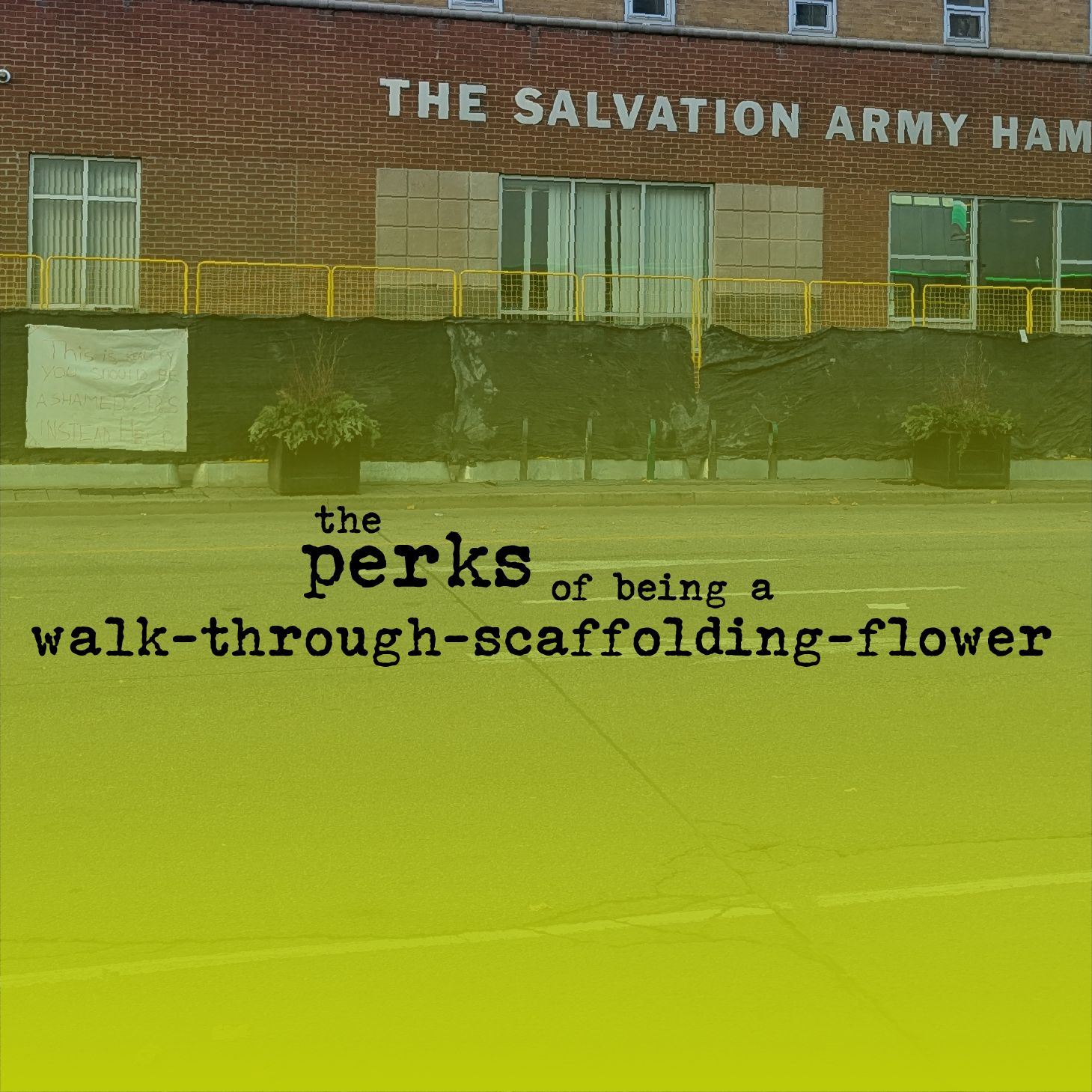

- The perks of being a walk-through-scaffolding-flower

The perks of being a walk-through-scaffolding-flower

Charity, entertainment, order.

The perks of being a walk-through-scaffolding-flower

Photo by author - Edited by author

There was an opinion article in a recent edition of the Globe and Mail that you may have missed. It made the rounds on social media, sparking the kind of intense debate likely sought by the editor that approved it. Penned by the politically ambiguous/casually conservative columnist Robyn Urback, the article - entitled “Cities have normalized delinquency” (running under other names online) - rails against today’s municipal governments for ignoring the “signs of social decay” all around us.

Even as opinion pieces go, the article is unbecoming of the Globe. It is so full of right-wing populist talking points, there’s little room for any of the vague and cherrypicked “won’t somebody think of the children!?” examples Urback shoehorns in to offer the appearance of substantiation. Urback makes claims that “social activists” are forcing encampments and public drug use on a terrified public against everyone’s will and without the consent of the community.

Just a quick sidenote, but every progressive activist I know would go to great lengths to have even 1/10th the power those on the right think we have. All of us are sitting out here, desperately waiting to find a sliver of a percent of a chance of gaining even a modest electoral victory while the populist right claims we’ve assumed control over every last institution and organization in society. Absolutely and unreservedly bizarre claims, if one assumes they’re made in good faith and not just strategic hyperbole to whip the base into a lather.

Urback’s article is chalk full of arguments that would get a first year J-School student a C- on a midterm paper. The columnist conjures an army of woke strawmen to do battle against: “You don’t support a safer consumption site metres from a school? Well then, you must be okay with drug-users dying. You want encampments forced out of parks? How would you like to be forced out of your home?”1 To whom are you speaking, friend? Ma’am, this is a Wendy’s.

The column avoids any tough observations about the why of the matter, offers no discussions about the drug crisis, makes no effort to discuss the housing crisis or the unwillingness of the provinces and federal government to come to the table with a meaningful solution and funding package. Urback offers little more than the same kind of conservative anger that’s been bubbling since the onset of the COVID-19 Pandemic - an anger that’s propelling the council campaigns of the next generation of conservative activists who see the issues of crime and homelessness as their ticket to lifelong electoral success. You know, the horde of late 30’s/early 40’s “I’m just a big strong dad here to protect my helpless wife and kids” types.

Urback offers a “solution”, though, which extends no further than supporting Toronto’s right-wing populist mayoral candidate (and prototype of the “oh so strong manly man super straight macho little buff dad” candidate) Bradford Bradford’s crusade against deviants and delinquents. Adding to this, Urback makes unspecified calls to “clean up our public spaces”, enact ‘zero tolerance’ policies for drug use in public, “stop using stupid euphemisms like ‘unhoused’ and get real about what’s happening.”2 The piece veers about as far from supporting evidence-based policies and long-term solutions as you can get, but real policies certainly get in the way if your goal is to sell papers by kicking those imagined “woke social engineers” in the teeth, right?

The article is divisive and silly (and John Lorinc offers a very good urbanist critique of it in Spacing which I highly recommend checking out). Despite this, it also reflects a mood in cities in the present moment, namely that today’s urban areas are characterized predominantly by disorder. Urback says as much, writing that we must get tough on people experiencing homelessness because doing so “is not simply a matter of restoring the use of public spaces for everyone, but restoring a sense of order.”3

Order.

That word is going to come up a lot in our politics from now on. A great many eager politicians will present themselves as the champions of order, vowing to use force to crack down on the “delinquents” that Urback and the populist right blame for the ills of society. No more drugs, no more visible homelessness, no more graffiti, no more litter, no more crime. Just order.

Of course, many of the solutions presented by these champions of order are little more than thin façades intended to hide, shuffle, or relocate problems instead of actually addressing them.

Here in Hamilton, we were treated to a very real example of exactly that when, in the days before the much-hyped grand re-opening of Copps Coliseum, a strange bit of “scaffolding” went up in front of one of the venue’s neighbours - a neighbour that long, long predates the newly repainted entertainment venue and that has been struggling to provide help where it is most needed.

***

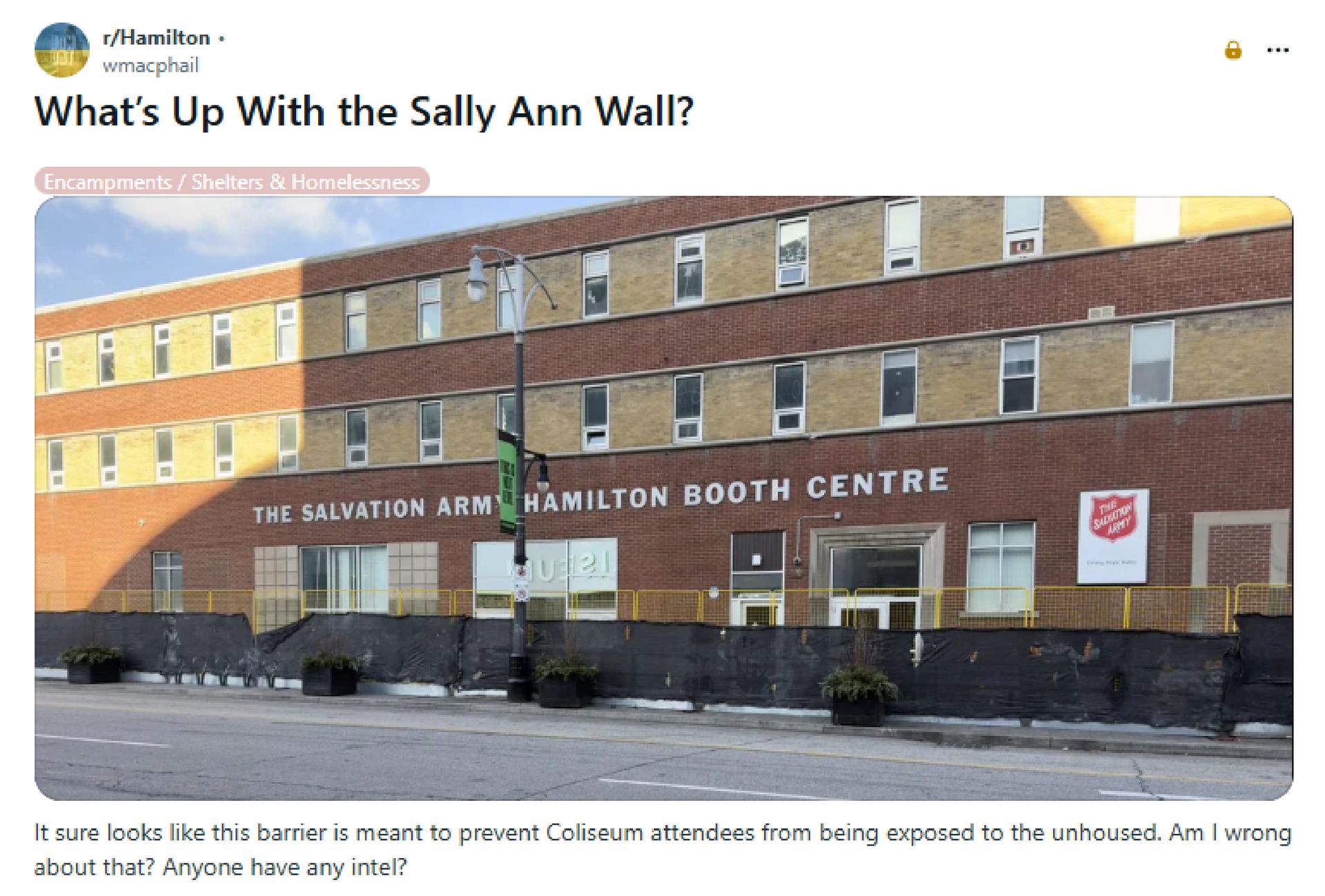

On Wednesday, November 19, the Strathcona-based writer and photographer Wayne MacPhail posted a photo to the r/Hamilton subreddit with the headline “What’s Up With the Sally Ann Wall?”

The photo shows the front of the Salvation Army’s Hamilton Booth Centre, partially obscured by yellow crowd control fencing. The fencing is adorned with thin sheets of coarse black material. A collection of decorative planters serve to both break up the monotony of the scene and provide reinforcement for the wall. Information provided later indicated that the wall, despite looking worn, had been put up in the early morning hours on the same day.

In the post, MacPhail asks: “It sure looks like this barrier is meant to prevent Coliseum attendees from being exposed to the unhoused. Am I wrong about that? Anyone have any intel?” By the time the post was locked by the subreddit’s admins, it had 108 comments ranging from outrage at the callousness of the wall to unequivocal support for it and whatever harsh measures can be implemented next. Two commenters independently used the opportunity to call downtown a “cesspool”.

Reporting from Joey Coleman and from Teviah Moro at The Spec helps to fill in the gaps. The Hamilton Urban Precinct Entertainment Group (HUPEG) - the private consortium which has signed a lease with the City of Hamilton giving them total control over downtown’s largest entertainment venues until 2070 for the hefty sum of $1 a year and a property tax exemption on all but 0.28% of the assessed $80.4 million value of their holdings4 - requested a permit to install the wall. HUPEG is calling the wall “walk-through scaffolding” that will, in their words, “ensure public safety is maintained within the right-of-way while work is underway.” The “work” referenced there is apparently going to happen to the façade of the Booth Centre, though explanations could not be provided as to how the fencing, which is on the sidewalk and around 1.5 metres away from the front of the building, would protect anyone from any overhead work, nor was there any indication as to how the visual barrier (in the form of the black fabric on the outside of the fencing, facing the Coliseum) would keep people safe from dangers like falling bricks or paint cans.5

***

HUPEG bills itself as a “regional consortium” led primarily by the Carmen’s Group and the Mercanti Family, with LiUNA, the Meridian Credit Union, and Paletta International (now the Alinea Group) rounding out the main players. The goal of HUPEG is to create a "Distillery District-inspired area” complete with entertainment, commercial space, and residences, calling the renovations to the Coliseum and surrounding venues a “generational city-building project”.6

The presence of the Salvation Army’s Booth Centre rather obviously complicates this goal.

The folks behind HUPEG have expressed a desire to see the Booth Centre relocated for years. Back in 2021, when HUPEG was just getting started on its “generational city-building project”, some of those involved indicated that conversations had kicked off with the Salvation Army about their finding a new location to help, as Spec columnist Scott Radley noted in an article, “redefine this part of the city and give it a more upscale feel.” In the same article, HUPEG representatives stress the Booth Centre was not being “forced” to move, but that discussions were “underway with a number of property owners in the downtown to see if there’s a spot that would fit the needs of the men’s centre.”7

A year later, the idea of a relocation came up again, with HUPEG representatives noting that “Cities have to have social services, and cities have to have arts and entertainment. You want them to be in the most optimized locations.” Then-Mayor Fred Eisenberger was characteristically blunt in his assessment, saying the Booth Centre is “out of sync” with HUPEG’s redevelopment plans. But, again, HUPEG stressed the Booth Centre was not going to be forced to move and the Salvation Army said it had no plans to relocate.8

Things became slightly more serious in 2023 when a consultant’s report on the Hamilton Farmer’s Market included a surprise reference to “construction/disruption” to the Booth Centre between 2025 and 2030. The Salvation Army was apparently caught off guard by this, saying that, as far as they knew, it was “status quo for the Hamilton Booth Centre.” The folks behind HUPEG quickly denied providing any information to the Farmer’s Market consultants either, further deepening the mystery.9

The mystery cleared up a month later when the agreement between the City of Hamilton and HUPEG was released by council. Buried in the fifth chapter of the agreement is clause 5.10, which reads:

5.10 - Salvation Army

HUPEG will act in good faith and use commercially reasonable efforts to relocate the Salvation Army away from its 94 York Boulevard location to another site that is acceptable to the Salvation Army. To assist HUPEG, the City shall act in good faith (but at no cost to the City) to facilitate the relocation of the Salvation Army to a site that meets the Salvation Army’s and the City’s broader programming objectives.

The Salvation Army, once again, expressed shock that they were included in the agreement and stressed they had “no intention at this moment of relocating.”10

Then, in June of 2025, came another surprise announcement, this time that the Salvation Army and HUPEG were actively collaborating to explore a relocation of the Booth Centre with help from the City of Hamilton (in essence, exactly what was laid out in 5.10 of the City’s agreement with HUPEG). Months later, with the grand re-opening on the horizon, HUPEG reassured councillors and the public that safety would not be a concern for those attending events at the newly rebranded “TD Coliseum”. While some members of council raised the idea (without providing any evidence) that crime in the city was out of control and that people experiencing homelessness constituted an “elephant in the room”, the folks behind HUPEG that everything would be fine for the big launch. At the same time, they told the Spec they were “not in a position” to comment on the Booth Centre.11

And then, on November 19 - just 48 hours before HUPEG opened the doors to TD Coliseum, welcoming fans in for the venue’s first real public performance by none other than the legendary Paul McCartney - up went the “walk-through scaffolding”. The permit for the “scaffolding” is apparently valid until late January of 2026.12

The Salvation Army’s Booth Centre long predates HUPEG. In fact, the current Booth Centre building predates even Copps Coliseum by 35 years. The Salvation Army’s presence in that location goes back so far, they were a fixture on York Boulevard when that particular part of the corridor was still called “Merrick Street”.

So let’s back way up to better understand the Salvation Army and its presence in Hamilton.

The Salvation Army is a derivation of Methodism, the Protestant orientation that believes in “sanctification” (spiritual maturation to the point of acting and living out of “pure love” for God and the elimination of original sin), “works of piety” to help achieve sanctification, and “works of mercy” for those who are suffering. Readers will note that I attended Catholic school and have had to do a lot of reading to even come close to understanding all the different flavours of Protestantism, so I hope that brief description does Methodism justice.

The Salvation Army itself was founded by William Booth, a preacher who trained in the Methodist tradition, but balked at the rigid confines of the religion as it had been organized. Setting off on his own (with his wife and a few followers), he established a Christian mission in London’s impoverished east end where he combined proselytizing with acts of charity. Booth and his followers built a movement that, by 1878, had begun calling itself the “Salvation Army”, modelling the church after the military and using on-the-street acts of charity and marching bands to draw attention to their cause. Ever the underdogs, the Salvation Army gained a legion of detractors, with opponents claiming Booth was out to exploit the poor and undermine the Anglican Church. One Conservative MP even went so far as to label Booth the “anti-Christ” himself.

The Spec first makes note of Booth’s movement the same year they started using the Salvation Army name, 1878, including an update on their activities in a section called “Miscellaneous Items”, which recounted curious goings on from around the world in the form of one-to-three sentence briefs. Amidst reports about the wonderful teas of Ceylon and declining marriage rates in Prussia, the Spec noted that Booth’s “Salvation Army” - in particular his “body of lady preachers” - had been “causing some excitement in the north of England.”13

A few short years later, the Salvation Army had begun to establish a presence in Hamilton, albeit to the chagrin of local institutions. On the morning of June 14, 1882, a group of Salvationists brought their instruments to the Great Western train station (roughly where today’s West Harbour station is) and began an impromptu concert to raise awareness of their cause. The station officials present were having none of that sort of thing and promptly shooed the musical evangelizers off the property.14

The following year, the Spec reported that “The Salvation Army does not appear to get along very well here,” noting an unsourced conversation “overheard” by a reporter. The conversation, purportedly between two women, concerned their interest in attending one of the Salvation Army’s “hallelujah meetings”. One of the women wanted to attend to see what it was about, to which another replied “I can’t go; my husband wouldn’t let me…he’d rather let me go to Madame Rentz’ minstrels than to one of those meetings,” referencing the salacious all-female singing and dancing troupe that performed in tight-fitting clothes (there’s no evidence they performed in blackface, appearing to trade that upsetting trend in entertainment at the time for a more scandalous form of sex-forward act).15

For the first few years of the Salvation Army’s presence in the city, they moved with some regularity. Their primary meeting hall - called a “barracks”, in keeping with the military terminology - shifted from a space on Ferguson in 1883 to a location at the corner of King and Catharine in 1884. By 1885, the church had raised $5,000 (approx. $150,000 today) to build their own local barracks at 3 Hunter Street East, near the street’s intersection with James Street South (across from today’s Hamilton GO Centre). They moved into their new location in February of 1886, accompanied by four brass bands and hundreds of well-wishers from barracks in neigbouring communities.16

***

In 1883, an irate Hamiltonian named Mrs. Gaskell burst into the Salvation Army’s barracks on a Sunday morning in June, interrupting their service with a tirade against the organization. This was, later reporting would claim, something she did on more than one occasion. Shouting at the assembled Salvationists, Mrs. Gaskell, according to the Spectator, “made a number of charges against the Salvation Army. She called the barracks a den of iniquity and said all the toughs of the city congregated there.” Mr. Gaskell had, evidently, begun spending what Mrs. Gaskell considered all-too-much time at the barracks, particularly with select female congregants. One of said congregants, a Nellie Kiezer, informed the Spec that “Mrs. Gaskell is a very jealous woman,” but that the two had a frank conversation and come to an understanding about Mr. Gaskell’s…devotion to the cause.17

Mrs. Gaskell’s interjection represents just one of dozens of instances of disorderly (ah, there’s that word again) conduct that proliferated around the barracks of the Salvation Army. Before their move to Hunter Street East, residents living around their first meeting hall on Ferguson made a public plea to the Hamilton Police for help clearing the sidewalk of the “young gentlemen that hang around the door” of the barracks for the sake of the women in the neighbourhood. The various barracks of Hamilton featured prominently in the more scandalous columns of the Spec with reporters telling tales of fist fights, drunken outbursts, and dramatic late-night arrests of wanted criminals. There was more intense drama at barracks across Canada; a disagreement between two worshipers ended in a knife fight at a barracks in Essex County, a barracks in Quebec City was bombed by upper class hooligans while Salvationists were in service and, in London, a deliberate fire destroyed that city’s barracks, which happened to be one of London’s oldest buildings, having started off as a Congregationalist church in the early 1800’s.18

As the church began to establish itself, the scandalous behaviours associated with its meeting halls began to drop off. In Hamilton, this tempering of passions happened when the local Salvation Army was informed their barracks was not long for this world.

The barracks on Hunter Street was, unfortunately, in the way of the redevelopment of the city’s downtown train station. In 1895, the Toronto, Hamilton, and Buffalo (THB) Railway bought the barracks and all the homes along Hunter Street between James and John to make way for their new station, quickly demolishing them so they could get to work.

The church found refuge in a tiny hall on MacNab Street while they negotiated the purchase of a lot at the southwest corner of Hughson and Rebecca (where today’s New City Church is located). Within a year, the site had been secured, plans had been drawn up, and the Salvation Army was advertising their forthcoming digs with quaint illustrations in the Spec. The new location - eventually upgraded from a barracks to a “citadel” - opened to the public on Saturday, May 23, 1896, with the Spec reporting that those worshiping within would, for many years, “battle against the hosts of evil and give many a hard knock at Satan.”19

The Salvation Army’s churches served multiple purposes. They were places for religious services, halls for community events, centres from which they could coordinate their outreach efforts, and shelters for those in need of a place to stay. By 1908, the organization was running a soup kitchen out of the Rebecca Street citadel. The church distributed 400 baskets of fresh produce, staples, bread, and beef to the needy across Hamilton for Christmas that year, funded through their new program of collecting money in open kettles near newsstands in the city.20

The following year, just before Christmas, the leaders of the church announced that the Salvation Army had completed the purchase of 94 Merrick Street, the former Walter Woods Broom factory. Their intention was to turn that building into a shelter they called the “Men’s Metropole”. The Salvation Army’s proposal was to house around 60 men who would work in the salvage and reuse store they planned to operate on the premises.

In early February of 1910, officers of the Salvation Army brought a request to city council to support their efforts with a $1,000 grant. The meeting - which dealt with, as the Spec phrased it, “the tramp question” - saw members of council and affiliated civil servants provide comments entirely reminiscent of debates that still rage in the city. The city’s Chief of Police speculated that the Metropole’s “inception would be advertised all over the country, and there was a danger of the tramps flocking to the city.” The mayor believed that many of the city’s “vagrants” were married men with children who “were not inclined to the supporting habit.” And, of course, council ultimately deferred the decision until they could study how the Salvation Army’s operations in Toronto worked.21

The Metropole opened on Monday, April 18, 1910 before council could decide on providing financial support. Two weeks later, council met and voted to deny the grant to the Metropole because, in the words of a member of the Board of Control, “it is a good institution, but this is a matter of business.”22

Two months after the Metropole opened, an out-of-work cigarmaker who had taken up lodging at the shelter was found dead in his room. While the official ruling was that he died from heart failure, his passing was a less-than auspicious event in the early days of the Salvation Army’s charitable mission on the site it still occupies to this day.23

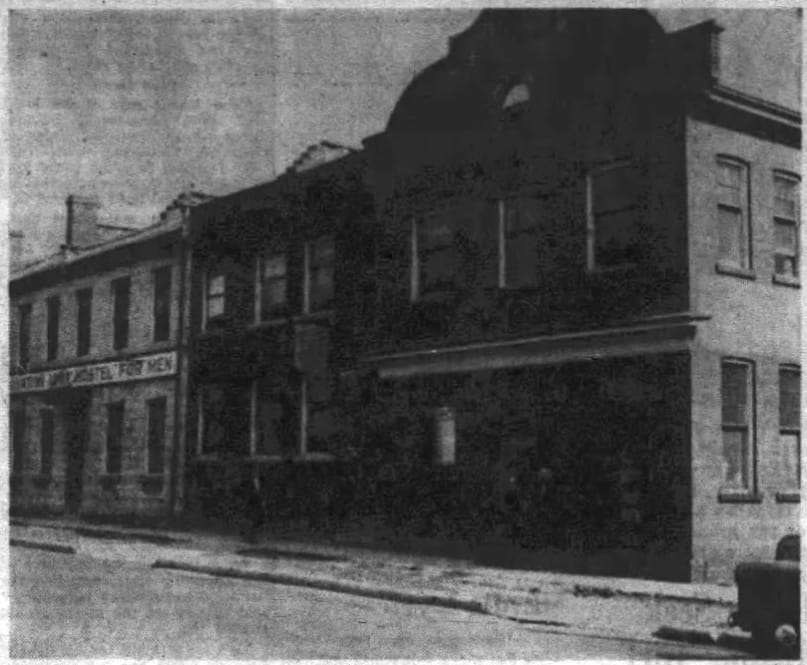

The Salvation Army Men’s Metropole as it looked in 1949 just before its demolition. The building on the far left - a former broom factory - was the original site and was expanded when the structure in the middle and on the right of the photo were added. These buildings were replaced by the current Salvation Army Booth Centre in 1950. Photo from the Spec, June 21, 1949.

***

The Salvation Army played an outsized role in the First World War, coordinating distributions of care packages for soldiers, providing food and shelter on the front lines, and offering combatants spiritual guidance amidst the horrors of war. It was during the First World War that Canadian soldiers began referring to the Salvation Army by an affectionate nickname: the Sally Ann. There is debate as to whether this is because of the organization putting women front-and-centre of their religious and charitable work, or if it was simply a catchy little moniker with fewer syllables.

On the homefront, the organization had ingratiated itself with everyday people thanks to their steadfast commitment to the war effort. In the dying days of the war, after a successful drive to send tents to soldiers, the Spec reported that the city was forever grateful for the organization; “Hamilton has always a warm spot in its heart for the Salvation Army,” a reporter observed, reflecting just how much attitudes had changed in the 35 years since the paper first began reporting on the church’s efforts to recruit in the city.24

As soldiers returned home, they brought with them a deep affinity for the organization, which had kicked its charitable efforts into overdrive. Indeed, their mission was an important source of relief after the Great Depression hit the city. By 1931, their religious services took on the feel of political rallies; a service in late March of that year saw representatives from the city’s military, commercial, charitable, and industrial concerns, along with ministers from other Protestant denominations, participating in what was billed a “mass meeting”, over which Mayor John Peebles presided.25

The local Salvation Army ended up providing much of Hamilton’s outreach to the unemployed during the Depression. This would bring it into conflict with a municipal administration committed to economizing their way through the crisis. In December of 1932, the Salvation Army sent correspondence to the city about their charitable efforts from the year before. In it, they noted how they provided 900 daily meals and 260 nightly beds to “unemployed single men” in the city. Conservative Ward 4 Alderman George Hancock took issue with this, telling council that the program, “the cost of which had been paid by the city, was not fair,” presumably because of the charity’s focus on unemployed men without families. On Hancock’s urging, council voted to instruct the Board of Control to respond to the Salvation Army expressing concern over the matter.26

Through the Depression and the Second World War, the Men’s Metropole continued to provide relief to those in desperate need. By 1946, the Salvation Army reported that, in the first 10 months of the year, they had already provided beds on over 40,000 occasions and fed 2,770 meals to those in need. The organization warned that a great many of the permanent residents on Merrick Street were the elderly who could not afford a place to live on their own.27

***

In 1949, the Salvation Army celebrated 55 years of service in Hamilton, revealing to the community that, since their Merrick Street mission opened (which had been renamed from the Metropole to the Men’s Hostel) in 1910, they had served 1,792,140 men. And need was only growing. With approval from the higher-ups in the church, the Salvation Army decided to demolish the existing structure on Merrick Street and build a new, larger capacity shelter that could accommodate up to 180 men a night (that number would drop to 150 after adjustments were made during construction). The new building would include a recreation room, a kitchen, showers, upgraded washroom facilities, and work space for those seeking refuge. Though many in the community lamented the loss of the original building (deemed a “city landmark” by the Spec), the chair of the local Salvation Army stressed that “the need for new facilities could scarcely be exaggerated.”28

In one short year, the new building - the Salvation Army Men’s Social Service Centre - was ready to begin accepting those in need.

On September 12, 1950, the building was formally opened when Bill Goodfellow, the provincial Progressive Conservative Minister of Welfare, unlocked the doors in a ceremony which included Mayor Lloyd Jackson and representatives from social service agencies across Hamilton. In a moralizing speech at the event, Goodfellow reminded those gathered that, while “there was a responsibility on the part of citizens to help those needy persons unable to help themselves, there was no responsibility to help any able-bodied person” and that there was a “growing tendency to depend on government aid” which, he believed, “would result in the loss of Canadians of their initiative and thrift.” While Goodfellow offered a healthy dose of conservative individualism, Mayor Jackson took a different approach (possibly informed by his own Liberal orientation), praising the Salvation Army as “an integral part of Hamilton life” and a model of “practical Christianity”. And, with that, the new mission was declared open.29

The building, though open, was not entirely complete. A fundraising campaign to provide the Men’s Social Service Centre with all it needed was, in the Spec’s phrasing, “abruptly suspended” in May of 1950 when the Salvation Army refocused their efforts on collecting money to support those impacted by devastating floods in Manitoba that year.

In 1952, the Salvation Army relaunched their original campaign under the leadership of former Ward 1 alderman Bessie Hughton, hoping to bring in close to $100,000 (around $1.2 million today) to complete the Merrick Street centre and support Grace Haven, their home for “the unmarried mother and her baby” on James Street South (roughly where today’s St. Joe’s emergency room is). The need for more resources was made clear amidst the campaign when the administrators of the Men’s Social Service Centre reminded Hamiltonians that “the hostel is always crowded to capacity, with accommodation strained to the limits.” That year, the Spec was filled with articles about the work done at the Men’s Social Service Centre; articles profiled the men who had been provided a job opportunity after a stay at the hostel, men who struggled with alcohol but had begun to counsel others after becoming sober, of the prisoners helped when they had no where else to turn after completing their sentences. The campaign managed to bring in around 65% of their goal, far less than expected due to a shortage of canvassers and the strain of the Korean War on the community.30

The need for the services offered at the Merrick Street mission only grew as time marched on. In 1958, the shelter served over 62,000 meals to those in need. The next year, the number had ballooned to over 84,000. Into the 1960’s, those overseeing the city’s social services continually reported a growing number of people in need. By 1963, there were 20 Salvation Army social service organizations in Hamilton, providing thousands of meals each year. Need grew, but the size of the Merrick Street Men’s Social Service Centre did not.31

A story from a snowy evening in March of 1966 puts that fact in perspective. With the temperature below freezing, the Men’s Social Service Centre was, once again, full. When an elderly man, drunk and without lodging, sought a bed, he was turned away by staff who informed him there was no space left. He stumbled out into the street where he encountered two Hamilton police officers. “Arrest me or I’ll break a window,” he told them, hoping to spend the night in a warm jail cell instead of on the street. The officers refused, so the man, with his bare fists, began pounding on the windows of the shelter. When one broke, the officers finally took him in. He was swiftly sentenced to three months for vandalism.32

Instances like that would only increase in regularity. In the late 1960’s, a decision was made to “deinstitutionalize” people in psychiatric facilities. These institutions, flawed as they were, served as a home for many with complex mental health challenges. For many, these were the only homes they had ever known. When deinstitutionalization began, countless numbers of patients fell through the cracks and into the lap of the Sally Ann.

Growing need also meant the Salvation Army had to spread its scant resources thin. In the spring of 1971, conditions at the Men’s Social Service Centre had deteriorated. People accessing services there complained of rampant theft, soiled bedding, a “jail-like atmosphere”, and non-existent recreation programming. The Hamilton Welfare Rights Organization, a militant group that had begun making a splash in the city the year prior with their pickets of municipal buildings and social assistance offices, organized a protest in front of the Merrick Street shelter. The program lead at the Men’s Social Service Centre told the Spec, “this is the first time we’ve ever been picketed.” The protest garnered some positive results, with the Salvation Army committing to better cleaning and more consultation with those staying in the shelter.33

***

As Hamilton’s grand downtown urban renewal project blasted and smashed its way through the core, the world around the Men’s Social Service Centre kept changing. York Street became York Boulevard and was rerouted at Bay Street into what was once Merrick Street. That meant that, in 1976, the shelter’s address was updated from “94 Merrick” to the “94 York” we know today.

The city marched into the 1980’s and downtown kept changing. After a $180,000 renovation to the Men’s Social Service Centre, a Spec profile outlined what the Sally Ann dealt with on “Skid Row”. Foreshadowing what was to come, the reporter observed that, “in recent years the rehabilitation program has assumed a greater importance, as those in need of the Salvation Army’s careful concern have become younger.”34

The Centre faced two serious threats over the next few years. When the provincial government began advancing their GO Advanced Light Rail Transit (ALRT) project - an elevated, automated, cartoonishly retro-futuristic intercity rapid transit concept - they focused on a route that would have seen the sky high trains run down York Boulevard and along a path that intersected with some of the Salvation Army’s buildings on the street. The Centre’s facilities were saved when the provincial government mercifully abandoned the strange project in 1985.35

And then there was the far more personal betrayal of Herb Kelly. On July 22, 1991, Kelly, the newly promoted director of addictions and rehab at the Men’s Social Service Centre, told colleagues he was leaving early for an appointment. Those who attended the programs put on by Kelly described him as an “affable” and “charismatic” man who understood what they were dealing with, given that Kelly was, himself, a recovering alcoholic. Even if he told people in the program that he had a history of using stolen credit cards and gambling excessively at casinos around Canada and the United States, the men he counseled still trusted him. The trust was so deep that many described him as a close friend. That’s probably why, when he told participants that, as part of their journey toward sobriety, they should entrust him with their money to prevent them from purchasing alcohol, many handed their savings over willingly.

Kelly never returned from that doctor’s appointment. Indeed, after collecting nearly $8,000 from the addicts he was supposed to help, Herb Kelly skipped town and was never heard from again. The case remains unsolved to this day.

It took a year before the Salvation Army’s rehab program was back to where it was before Kelly’s disappearance. But, even then, damage had been done. Kelly’s replacement told the Spec, “coming here, the biggest problem I found was that trust had been violated…they’d put a lot of trust in this person, and he basically destroyed all that.”36

***

Later in 1992, the federal government struck a deal with the Salvation Army to serve as a temporary halfway house for criminal offenders. The program was immediately controversial, but became even more so when, in August of 1993, a paroled violent offender walked away from a rehab program at the Men’s Social Service Centre. The offender made his way to Sudbury where, in October of the same year, he shot a police officer. This event led the Canadian Police Association (CPA) to call for the closure of the shelter, saying that the “blood trail” led back to York Boulevard. The Salvation Army pushed back, saying it had not been appropriately informed of the offender’s violent past, which would have disqualified him from their programs entirely. Less than two weeks after the CPA made its demands, the Salvation Army announced the termination of their rehab program on York Boulevard. The shelter continued to provide refuge for those in need and host the halfway house program under its roof.37

The building was renamed the Booth Centre in 1996. This did little to detract from the controversy over the federal halfway house operating there. Heartbreaking articles about those living in the shelter long-term or a piece (once again refuting the baseless claims that “out-of-towners” were being shuttled into Hamilton to access our social services) that focused on how many working people lived at the Booth Centre because they were unable to afford the average rent in Hamilton of $790 a month (from the fall of 2000) did little to change public opinion.38

A violent attack on a store clerk in 2004 made matters worse. York Boulevard was busy on that morning in May when an individual staying at the Booth Centre as part of the federal halfway house program walked across the street to Jackson Square. The offender entered a store, attempted to assault the manager and, in the process, stabbed them repeatedly. There were complex mental health issues at play, but the community was shaken. Later that year, Mayor Larry Di Ianni received a commitment from the feds that the halfway house would be moved from the Booth Centre when their lease expired in 2006. After Fred Eisenberger defeated Di Ianni that year, he reiterated the call for the halfway house to go. It wasn’t until the start of Eisenberger’s second non-consecutive term in 2014 that the federal government announced it would close its 22 year “temporary” halfway house program by January 1, 2015.39

A few weeks after the COVID-19 Pandemic was declared, a person living at the Booth Centre tested positive for the disease, sparking fears that the strange new illness would seriously impact the city’s most vulnerable and change how social services were provided. The shelter was the centre of multiple outbreaks, including a surge in March of 2021 that saw around 60 cases at the Booth Centre. After multiple staff members became ill in 2022, the shelter began halting admissions.

As the virus swept through the community, healthcare providers needed to battle a second crisis; a spike in overdose deaths in 2022 saw four deaths at the Booth Centre and calls from community advocates for the Salvation Army to open a supervised consumption and treatment services (CTS) site on York Boulevard. The Booth Centre declined to participate and, a short while later, the provincial government all-but banned CTS sites.40

While the Salvation Army was dealing with those twin crises and Hamiltonians navigated our way through a world changed by the Pandemic, the city handed the keys to the Coliseum and much of the land in the 0.15 square kilometre, nine block chunk of the city’s core between Cannon, James, Market, and Bay to HUPEG for the creation of the Downtown Entertainment Precinct. And that brings us to today.

***

The Pandemic laid bare the crises in our community. A broken mental healthcare system, the abject failure of the war on drugs, the depths of cycles of poverty, the social abandonment of seniors, the unwillingness of governments to invest in desperately needed housing, a culture that venerates selfishness and consumerism while shaming those who fall through the growing holes in our social safety net. The York Boulevard Salvation Army has dealt with all of them from that very location where, 115 years ago, they turned a broom factory into a refuge.

When former Mayor Eisenberger announced that HUPEG had won the bid to renovate and control the city’s largest venues in 2021, he spoke of a post-COVID renaissance: “Once we're past the predominance of this pandemic, people will be yearning for entertainment,” he told the CBC.41 Judging by the attendance at the first few concerts at the new TD Coliseum, he was right.

But just because the people yearn for live entertainment doesn’t mean the massive, complicated, very visible problems that became so much worse during the Pandemic have gone away. Putting up “walk-through-scaffolding” and shielding concertgoers from crises with ugly black fabric won’t make things better. Nor will uprooting an institution that long, long predates the newly repainted Coliseum across the way.

The Salvation Army is not perfect (their past approach to members of the queer community has been deeply troubling, though they have begun to slowly make amends). The centre they operate at 94 York Boulevard is similarly complicated. There are very real concerns from many in the community about the quality of the care provided, the effectiveness of the organization’s strategy, and the inability of them (and so many other social service providers in the city) to adequately respond to the increasingly complex needs of those seeking help.

Hiding the Salvation Army behind a privacy barrier is no solution. Neither are the outraged calls for a return to “order” from the “bunch-o-dads” who will train their conservative anger at people in need during the next municipal election campaigns across Ontario.

For 115 years, the Salvation Army served as a helping hand on York Boulevard for those who fell through the holes in our social safety net. They’ve done what they could, even when the city has been less than supportive. Now, hidden behind “walk-through-scaffolding”, the future of the Sally Ann is in question. The holes in the social safety net are growing larger, the problems faced by the people who access their services are growing more complex, and the private interests who now control our city’s core are growing impatient.

The York Boulevard Salvation Army might be hidden from view, and it might soon be relocated, but the problems they exist to address won’t go away.

So when “just another neighbourhood dad” knocks on your door next year selling you their vision of “restoring a sense of order” to the city, ask yourself if their plans amount to little more than throwing a tarp up and hiding the real problems in our community. Ask yourself if they know the history of the agencies they demonize as part of the “poverty industry”. And ask if there might be a better way to address the crises we face.

1 Robin Urback. “Cities have normalized delinquency: There is nothing normal about an encampment forcing toddlers in the daycare next door to stay inside” Globe and Mail, November 22, 2025 (Link - Paywalled).

2 Ibid.

3 Ibid.

4 Matthew Van Dongen. “Hamilton releases details on multimillion-dollar ‘entertainment precinct’ deal with downtown developers” Hamilton Spectator, June 8, 2023 (Link - Paywalled); Teviah Moro. “Tax-free status transferred to Hamilton’s new arena operator” Hamilton Spectator, March 18, 2024 (Link - Paywalled).

5 Joey Coleman. “Joey’s Notepad: There is a Sidewalk Occupancy Permit for Fencing at York Blvd. Sally Ann Shelter” The Public Record, November 19, 2025 (Link); Teviah Moro. “Barrier around downtown Hamilton shelter sparks questions ahead of Paul McCartney concert” Hamilton Spectator, November 20, 2025 (Link - Paywalled).

6 Christine Rankin. “City hands over operation of 3 key downtown entertainment facilities for up to 49 years” CBC Hamilton, June 9, 2021 (Link); PJ Mercanti. “Opinion | HUPEG offers update on arena, convention centre renovations” Hamilton Spectator, October 5, 2024 (Link - Paywalled).

7 Scott Radley. “Opinion | Downtown entertainment group would like to see Hamilton men’s shelter relocated” Hamilton Spectator, July 9, 2021 (Link - Paywalled).

8 Teviah Moro. “Major redevelopment is in the works for downtown Hamilton. Do shelters fit in?” Hamilton Spectator, February 24, 2022 (Link - Paywalled).

9 "". “It’s ‘status quo’ for Salvation Army despite city consultant’s mysterious ‘construction’ reference” Hamilton Spectator, May 8, 2023 (Link - Paywalled).

10 Matthew Van Dongen. “Hamilton’s downtown development deal includes ‘surprise’ plan to relocate emergency shelter” Hamilton Spectator, June 9, 2023 (Link - Paywalled).

11 Teviah Moro. “Salvation Army, development group explore relocation of York Boulevard shelter” Hamilton Spectator, June 24, 2025 (Link - Paywalled); Mac Christie. “TD Coliseum team ‘very confident’ downtown safety not a concern” Hamilton Spectator, October 23, 2025 (Link - Paywalled).

12 Coleman, November 19, 2025 (Link).

13 “Miscellaneous items” Hamilton Spectator, December 11, 1878 (Spec archive link - Paywalled).

14 “No concerts wanted” Hamilton Spectator, June 14, 1882 (Spec archive link - Paywalled).

15 “The Rambler” Hamilton Spectator, January 13, 1883 (Spec archive link - Paywalled).

16 “The Diurnal Epitome” Hamilton Spectator, February 10, 1886 (Spec archive link - Paywalled).

17 “Gaskell Redivivus” Hamilton Spectator, June 19, 1883 (Spec archive link - Paywalled).

18 Spec archives from May 8, 1883 (Spec archive link - Paywalled); June 2, 1885 (Spec archive link - Paywalled); November 24, 1885 (Spec archive link - Paywalled); October 18, 1886 (Spec archive link - Paywalled); March 24, 1887 (Spec archive link - Paywalled); January 26, 1888 (Spec archive link - Paywalled); November 20, 1890 (Spec archive link - Paywalled).

19 “The T.,H. & B. Station site,” Hamilton Spectator, May 21, 1885 (Spec archive link - Paywalled); “Dedicated the Citadel” Hamilton Spectator, May 25, 1896 (Spec archive link - Paywalled).

20 “Soup kitchen,” Hamilton Spectator, February 13, 1908 (Spec archive link - Paywalled); “Poor are well provided for” Hamilton Spectator, December 24, 1908 (Spec archive link - Paywalled).

21 “Offer shelter for the needy” Hamilton Spectator, February 2, 1910 (Spec archive link - Paywalled).

22 “A deserving cause” Hamilton Spectator, April 15, 1910 (Spec archive link - Paywalled); “No more grants to old employees” Hamilton Spectator, April 27, 1910 (Spec archive link - Paywalled).

23 “Died in his chair” Hamilton Spectator, June 20, 1910 (Spec archive link - Paywalled).

24 “Current topics” Hamilton Spectator, March 19, 1918 (Spec archive link - Paywalled).

25 “The Salvation Army Great Mass Meeting” Hamilton Spectator, March 29, 1931 (Spec archive link - Paywalled).

26 “Members are asked to give city aid” Hamilton Spectator, December 15, 1932 (Spec archive link - Paywalled).

27 “Salvation Army intensifies aid to unfortunates” Hamilton Spectator, November 26, 1946 (Spec archive link - Paywalled).

28 “S.A. Plans New Hostel On Merrick” Hamilton Spectator, June 21, 1949 (Spec archive link - Paywalled).

29 “Welfare Minister Opens Salvation Army Centre” Hamilton Spectator, September 13, 1950 (Spec archive link - Paywalled).

30 Spec archives from April 4, 1952 (Spec archive link - Paywalled); May 15, 1952 (Spec archive link - Paywalled); May 28, 1952 (Spec archive link - Paywalled); June 6, 1952 (Spec archive link - Paywalled); June 28, 1952 (Spec archive link - Paywalled).

31 Spec archives from May 4, 1960 (Spec archive link - Paywalled); January 3, 1961 (Spec archive link - Paywalled); April 27, 1963 (Spec archive link - Paywalled); March 24, 1966 (Spec archive link - Paywalled).

32 “No Room At The Hostel, Now ‘Guest’ In Jail” Hamilton Spectator, March 24, 1966 (Spec archive link - Paywalled).

33 “Sally Ann hostel is picketed” Hamilton Spectator, April 1, 1971 (Spec archive link - Paywalled); Malcolm Gray, “Brigadier defends the Sally Ann as hostel picketed,” Hamilton Spectator, April 2, 1971 (Spec archive link - Paywalled); “Protest gets SA sympathy” Hamilton Spectator, April 15, 1971 (Spec archive link - Paywalled)

34 Charles Wilkinson. “Army believes every person is worthy of another chance,” Hamilton Spectator, February 10, 1979 (Spec archive link - Paywalled).

35 Adam Mayers. “York is the way to GO: study” Hamilton Spectator, May 12, 1984 (Spec archive link - Paywalled).

36 Jill Morison. “Sally Ann employee vanishes with $7,750” Hamilton Spectator, August 30, 1991 (Spec archive link - Paywalled); John Mentek. “Drug program has a new look” Hamilton Spectator, August 30, 1991 (Spec archive link - Paywalled).

37 Spec archives from July 14, 1992 (Spec archive link - Paywalled); September 12, 1992 (Spec archive link - Paywalled); March 6, 1995 (Spec archive link - Paywalled); March 7, 1995 (Spec archive link - Paywalled); March 14, 1995 (Spec archive link - Paywalled).

38 Denise Davy. “Everyone knows Stan” Hamilton Spectator, July 15, 2000 (Spec archive link - Paywalled); John Mentek. “Sheltering the working poor” Hamilton Spectator, September 23, 2000 (Spec archive link - Paywalled).

39 Spec archives from May 29, 2004 (Spec archive link - Paywalled); November 5, 2024 (Spec archive link - Paywalled); May 8, 2006 (Spec archive link - Paywalled); December 20, 2006 (Spec archive link - Paywalled); December 6, 2014 (Spec archive link - Paywalled).

40 Spec links from March 30, 2020 (Spec link - Paywalled); March 10, 2021 (Spec link - Paywalled); January 7, 2022 (Spec link - Paywalled); December 10, 2022 (Spec link - Paywalled); June 13, 2023 (Spec link - Paywalled).

41 Rankin, June 9, 2021 (Link).